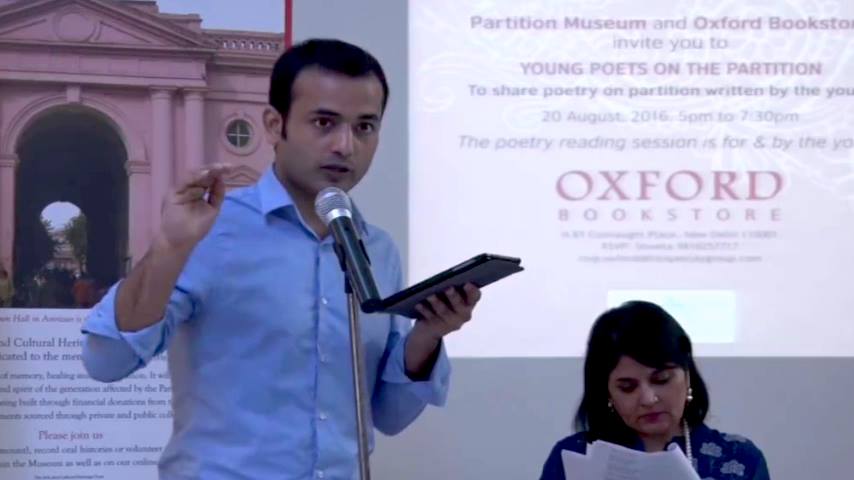

Field Notes: A photograph from my debut poetry reading at the Partition Museum project – Oxford Bookstore in Delhi / August 2016

War deadens you; street hardens you. I’ve seen boys beaten to pulp, and could do nothing to help them. I’ve come this close to getting smashed, cut or shot, and during those darkest moments of rage, considered violence, its violent delights. Art saved me. Somehow I would end up pouring all that vengefulness and anger, fear and blood, into whatever I was doing at the moment: drawing, journaling, poetry, screenwriting. And find peace. A kind of solace.

These three illustrations are from that turbulent adolescent period in Kathmandu when I played with colors more than words:

1. Wounded boy. First digital artwork. On MS Paint. 2005.

2. Motherland. Water color and crayons. 2006.

3. The Assassination of Gandhi. Ink on paper. 2006.

I hate to go back in time, but I must.

Past is never dead in “Shambhala,” my short story about the displacement of a Tibetan family. It’s a meditation on faith, poetry and violence, or displacement—the recurring themes in my recent publications and ongoing projects. Sometimes the only way to find out who you are as an “artist”—a term I use with great hesitation—is to talk about the themes and motivations behind your work.

“Shambhala” (Juggernaut, 2016)

“Shambhala” is a story of Tibet, a story of a people who have had to abandon their homeland. It’s also my story, story of my love for Tibetan myths, Chinese philosophy and poetry, which started early in my teens. I went to school in Kathmandu—the other home of Tibetan refugees. As an ethnic Indian boy who grew up in a Khas-Newar city, the sense of wonder, displacement and alienation depicted in the story is as much mine as it is Tenzin’s or Niu Jian’s.

When I was 18, I took refuge in Dhamma. Over the years, I have attended short and long Vipassana meditation courses, and have begun to combine it with Samatha practice recently. “Shambhala” is a result of these experiences, and a deep yearning for reconciliation and understanding between the opposing classes of people. The meditation technique, which Tenzin practices to heal the self and history, comes from the master Thich Nhat Hanh. And it’s extremely effective for those looking for a way to vanquish persistent ghosts of the past from their body and psyche. To become one with peace and understanding through speculation and poetry.

—from my interview with Juggernaut

“Which species of bird is a drone?” (New Myths, 2017)

This poem is about the history of violence, past and future, documented through prehistoric massacres such as Nataruk in Kenya, the Kalinga War and Ashokan pillars, the rise and fall of empires in the subcontinent, science and superstitions, and (future) machines of war and destruction.

“Field Notes” (Strange Horizons, 2017)

“Field Notes” is about the tolls of identity and border, and the wounds of partition. The first draft of the poem was written as snapshots, standing, as I got lost in the chaotic streets of old Delhi, searching for the home of a predecessor, Mirza Ghalib.

I got a chance to read this poem at a reading organized by the Partition Museum Project and Oxford Bookstore in Delhi.

In “Which species of bird is a drone?” and “Field Notes” and several other poems, I am trying to be both literary and speculative—playing within conventions of the genres, and maybe stretch them a bit. After a few rookie drafts, “Shambhala” was my first serious attempt at writing slipstream fiction—that’s folklore, science fiction and fantasy, combined. When I reread the story recently, I could see why it was a tough sale—it was more literary than speculative in its first drafts.

“Fravashi” (Work-in-progress)

My short story about a Parsi superheroine, “Fravashi,” turned out to be another tough sale. It was more literary, and perhaps a little too short on scenes for the scope of the plot—as F&SF editor Charlie (Charles C. Finlay) suggested. I’ve contemplated reworking it, but haven’t managed yet. The story was running into novella length (10-12K) at one point, and I’m afraid that I haven’t quite mastered the art of dealing with anxieties and horrors of writing at such word length. Also, poetry has been my preferred medium, and I sincerely hope to be able to tell longer stories.

A hastily cut draft of “Fravashi” was shortlisted for Fellows of Nature (FON) anthology of the 25 top scoring stories of the FON South Asia Short Story Contest, 2016. Judges included luminaries of the literary world, and I’m very humbled and encouraged by the recognition. However, their initial contract was terrible—as confirmed by the reaction of writers and editors whose opinion I value and trust—and I didn’t sign it.

“Lakhen and Dragonflies” (La.lit, 2016)

In “Lakhen and Dragonflies,” identity, partition, war and occupation are no longer underlying themes; they explode to the surface to drive the plot.

Nepal is under Indian occupation—it’s officially an Indian state—and Chinese dragonflies—war ensects (micro drones)—have gone rogue. Children are dead, and dead are coming back (not zombies). The editor published one of the earliest versions of the story, which was sleek, but not as literary or complicated as the most recent version.

In early 2010, I left a feature film that I had co-written because of “creative differences”—I didn’t know the term at the moment. The film has been made and released. I don’t know if I was in the credits. I don’t know if I should care. The most recent draft of “Lakhen and Dragonflies” is more ambitious and longer. But I have agreed to write a second installment of the story from the previous draft. And I haven’t. Yet.

Escaping Forms of Violence

As a media-agnostic young artist, you can be exploited, misled and bulldozered. Don’t worry. It takes a while but you’ll learn to eject yourself out of toxic circles and work cultures. At this point in my life, I want to get work done. And if I don’t have a consistent output today, I know better than to blame others.

Mithila Review

Mithila Review is and has been one big ray of hope in my life today. SFF community has been a great refuge—and I sincerely believe it to be encouraging and nurturing not just for me but for many sensitive and caring souls around the world. We are a creative bunch. We have scripts that need to go on the floor. Stories that need to be polished and submitted for review. Poetry that need to be translated and sold. Art and graphic collaborations that need to go beyond outlines and storyboards. And then there’s the need to make money. To sustain oneself. To save our dreams and souls.

So if you can, please consider supporting us by backing us on Patreon; subscribing to our digital editions.

Thank you everyone for being part of my journey as a reader, contributor, editor, friend and patron. I sincerely hope to continue to be a part of your endeavors.

Love,

Salik

Leave a Reply