“The man is only half himself, the other half is his expression.”

“Who is the father of computer?” I asked my 9-year-old niece. “Charles Babbage,” she replied promptly. Then I asked her, “And who is the father of cinema?” “What is cinema?” the fourth grader asked me. “It’s the art of films,” I tried to explain but seeing the little girl perplexed, I changed the topic. We were soon talking about ants that had found their way into a cupboard where she had kept her candies.

The first thing that a man learns is the language of his people. The language of other arts is an acquired and a required skill. When I was in school, I learned about many great personalities but none of them were filmmakers. Why don’t we teach cinema to children?

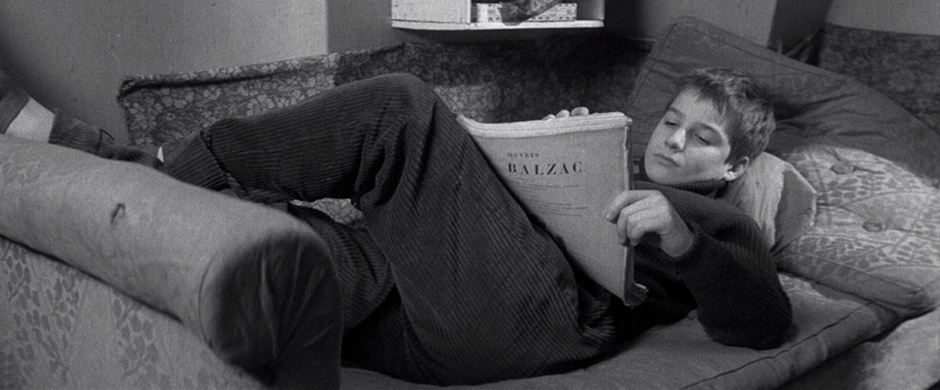

There is little evidence that we have understood this modern man’s expression. There are not many people who can ‘read’ films. Is this the reason why film history is still not a part of the school curriculum while other expressions are taught seriously? I discovered the new language of cinema very late during my adolescence. If anything, the idiot box was just a major distraction until my discovery of the cinematic language came along with the discovery of P2P and bit torrents. I had only heard about Satyajit Ray until I was 18. The Apu Trilogy was my first download; The Bicycle Thief was second. Sadly, a majority of us are not unaware of the many potentials and powers of the cinematic medium. But I can at least feel satisfied that I’ve already started.

While Ray was a redefinition of what cinema could be, there was one film that just changed everything for me. I don’t know whom to thank for the inspiration or the creation of this great art form; cinema has no such patron deity. It is truly modern. But I worship Ingmar Bergman anyway; it was his persona, his partnership with cinematographer Sven Nykvist that convinced me that cinema is the art of all arts and it warrants a serious study like other ‘expressions.’

The technology that limited the faculty earlier is no longer an issue. The Kerala State Chalachitra Academy, for one in South Asia, has already taken steps to make cinema an integral part of the school curriculum. NJ Nair wrote in The Hindu this January that the academy has proposed teaching the aesthetics of cinema, the technical aspects of filmmaking, including cinematography, editing and sound recording, in the vocational higher secondary education.

“Students should have a serious approach to cinema and they should learn it like literature itself. While appreciating the intrinsic artistic worth of cinema, they should be able to make use of its employment potential too. Hence, we have mooted a serious study of the technical aspects at the higher secondary level,” the academy vice-chairman VK Joseph told the newspaper.

Ronald Bergman started a similar discussion on The Guardian blog. He writes: Schoolchildren should be taught how to “read” films just as they are taught to read literature. They should learn how films systematize time and space and communicate ideas and emotions; how the patterns and structures of film genres allow us to engage specific historical and social rituals; how different conceptions of film history can direct and shape our responses; how film theory is a pragmatic extension and intensification of our interactions with a film, formal, technical and empirical. They should learn how to explore films from different angles and cultural perspectives.

“Why is film history not taught to schoolchildren?” The question must have occurred to many in the later half of the last century. A majority of us might consider it too modern a notion for our country. All great art form is modern in the true sense. Some might call it a dangerous proposition. All art is dangerous. Before our children begin to ask the same question tomorrow, let’s acquaint ourselves with the art of films. Let’s start “reading” films.